From zero to weirdo: How I changed everything in five years

Hello! If we haven’t met, my name is Teejay VanSlyke. I’m the reformed tech workaholic who semi-retired in his thirties to pursue a rich life of art, romance, literature, music, and daydreaming. After a decade of working myself ragged at tech startups and agencies, I decided it was time for a change. I was tired of living the life I thought everyone else wanted me to live. I saw friends who made much less money enjoying much richer lives and I wanted to understand why. Now that I do, I want to share my journey and help you live a more storied, adventurous life.

My transformation happened slowly and then all at once. It was 2018 and I was living in Portland, Oregon, in a fourth-story modern studio flat on a trendy street above bars, corner cafes, boutique pet stores, bakeries, and the like. I ironically called my apartment building the “Hipster Prison” because its front was adorned with metal grates that evidently helped filter incoming sunlight on its south-facing windows, thereby improving the building’s efficiency. What they actually did though, was made the building’s occupants feel like they were living in a trendy prison:

I adorned myself with the latest and greatest fashion, ate at trendy restuarants, and had a high-paying corporate job to pay for these privileges. My aesthetic mimicked the tenets of the minimalism trend that had become so prevalent in the 2010’s—white walls, simple furnishings, open floor plan, and five to ten books about how to live your best life, all in such pristine shape that any sane person would wonder if I had ever opened them. I was on the path to self-actualization. I believed that if only I worked harder and bought more expensive, beautiful things, I would “make it”.

But then, something curious happened. Out of nowhere, it was as if my mind rebooted. An engineering project of mine ended and I was left without work for a period of a couple months. Having worked so hard my entire adult life and having saved enough to subsist on for awhile without working, I dared to ask: What would it be like if I pressed the pause button for a bit? What if I didn’t try to find work and got to know myself? After having made my web engineering work my identity, I didn’t know what to do with all that free time. What’s more, I had no idea how to sit idle and watch the world go by. So I typed two fateful words into my search engine: “doing nothing”.

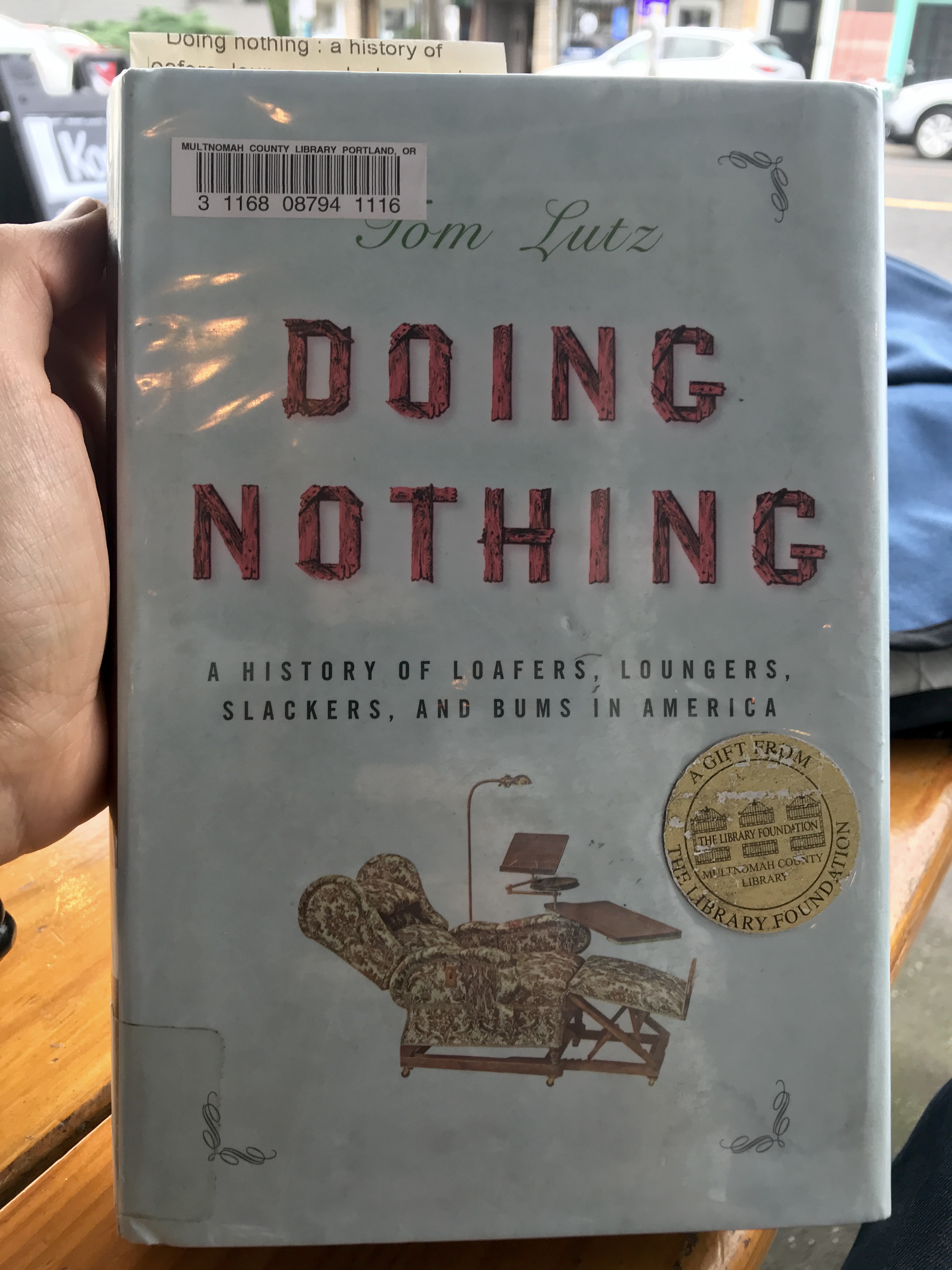

What I discovered was unexpected: There was a whole world of people writing about the art of doing nothing. There was Tom Lutz’s book Doing Nothing, a historical account of bums, loafers, & slackers in America. There was Bertrand Russell’s In Praise of Idleness, a treatise on the practical value of leisure and the evil our modern work ethic causes. And there was The Idler, a bimonthly magazine that extolls the virtues of slacking off and having fun.

I was hooked. Here was a cohort of writers challenging everything I had been taught about work my whole life. I realized my upbringing had left me neurotic, overworked, and incapable of stopping to smell the proverbial roses. But if I wasn’t going to take the time to smell roses, then why exactly was I working so hard?

I spent the next month poring over everything I could find. I researched the beatniks of the 1950’s, the hippies of the 1960’s, the slackers of the 1990’s, and the hipsters of the 2000’s. I found a common thread of self-proclaimed do-nothings who challenged the notion that a “respectable” career and family were the true path to contentment and fulfillment.

At the root of all of these movements was a broader social and cultural movement known as bohemianism. The term originates from the French bohème, which originally referred to the Romani people believed to have come from Bohemia, a region in present-day Czechia. The American writer Gelett Burgess described bohemianism thusly:

To take the world as one finds it, the bad with the good, making the best of the present moment — to laugh at Fortune alike whether she be generous or unkind — to spend freely when one has money, and to hope gaily when one has none — to fleet the time carelessly, living for love and art — this is the temper and spirit of the modern Bohemian in his outward and visible aspect.

Bohemianism places art, appreciation, romance, and merriment at the center of life by embracing simplicity and rejecting social expectations. It challenges the default cultural narrative of material accumulation and status anxiety.

As my research deepended, I began to make changes in my life. I filled my apartment with oddities: Strange fabrics, kitschy art, and junk I found in dumpsters. I diffused patchouli oil and started shopping at thrift stores, finding their contents to have so much more character and soul than the wares they were peddling at the boutiques on the high street. I discovered new locales—parks, quirky cafes, dirty alleyways—which my mind’s eye had suddenly invigorated with renewed meaning and beauty. I learned to play the ukulele—not because I wanted to start an exciting new musical career, but for the sake of itself.

For so long I had worshipped at the altar of the bourgeoisie. I believed whole-heartedly in the false salvation of material security and was ignoring my deeper, God-given propensity toward creativity, spirit, and contemplation. Our culture is organized around the idea that industry and productivity will save us. They surely have their place. We’ve got to eat. But our willingness to craft our entire identities around our job titles and cars and houses and watches and handbags and brands has diluted the rich broth of nutritive authenticity that simmers beneath our hardened façade.

Bohemianism can save the planet, your relationships, and you. By realigning your values away from consumption, competition, and conformity toward creativity, collaboration, and eccentricity, you begin to live a more dignified life. You reclaim your personal power and become true to your will. You come to see that accumulation of status symbols was a complex mask covering your own perceived inadequacies. To become whole is not to adorn yourself with lavish accessories, but to fortify your spirit with deep appreciation for life as it is.

When you shift your values in this way, you come to see that most of your previous efforts were bound to be futile. The promotions, the vacations, the designer clothes, the extravagant meals out were never going to lead you anywhere but to a deeper sense of dissatisfaction because your satisfaction was always a conscious decision, irrespective of circumstance. You begin to see more clearly that the good life is one born out of your deep creative power and requires little more than a room, some healthy food, modest clothing, and good friends.